On 16-Apr-2016 the Village of Cambridge celebrates the 150th anniversary of its incorporation. This series explores the events that led to the union of the West End and the East End. So far we’re learned that “the Corners” were physically separated by the Cambridge Swamp and logically separated by churches, schools, and stage coach routes.

The need for a fire department and a police department were forming the first steps toward a union. The 1864 East End fire destroyed much of the block on the north side of East Main Street between North Park Street and Division Street. The East End had no creeks from which to draw water to fight fires. The idea of a village water company was beginning to take shape.

Unable to wait any longer for the Corners to be incorporated into a village, Rufus King Crocker (R.K.), the editor of the Washington County Post newspaper, felt something must be done about providing a water supply to the residents. He campaigned hard and in the spring of 1865 the NYS Legislature passed the Crocker Act to incorporate The Cambridge Valley Water Company.

The plan was to use the water spring on Dr. Gray’s farm to provide drinking water and firefighting water to the Corners. It flowed year after year at a minimum rate of 100 gallons per hour, more than enough for the needs of the community.

But Mr. Crocker was 20 years ahead of his time. The economic depression that was setting in near the end of the Civil War made it hard to raise funds to invest in the new water company. [In fact, later Cambridge would be completely immobilized by the 1870s Depression]

But what really sounded the death knell for the proposed Cambridge water company was the driven-well or point. Northern soldiers during the Civil War avoided water contamination and stayed healthy by drinking water from an easily constructed wellpoint or drive point. This was a pipe with openings large enough to allow water to enter and small enough to keep the water-bearing formation in place. When the soldiers returned home, they replaced the repeated trips to the brook for fresh water with point wells. Many of the homes in Cambridge still have their point wells that were constructed in the mid 1860s.

[note: So, why does Cambridge today have an independent water company rather than a municipal one … trace it back to our inability to unite into a village in the early 1860s … and to the point wells that evolved out of the Civil War.]

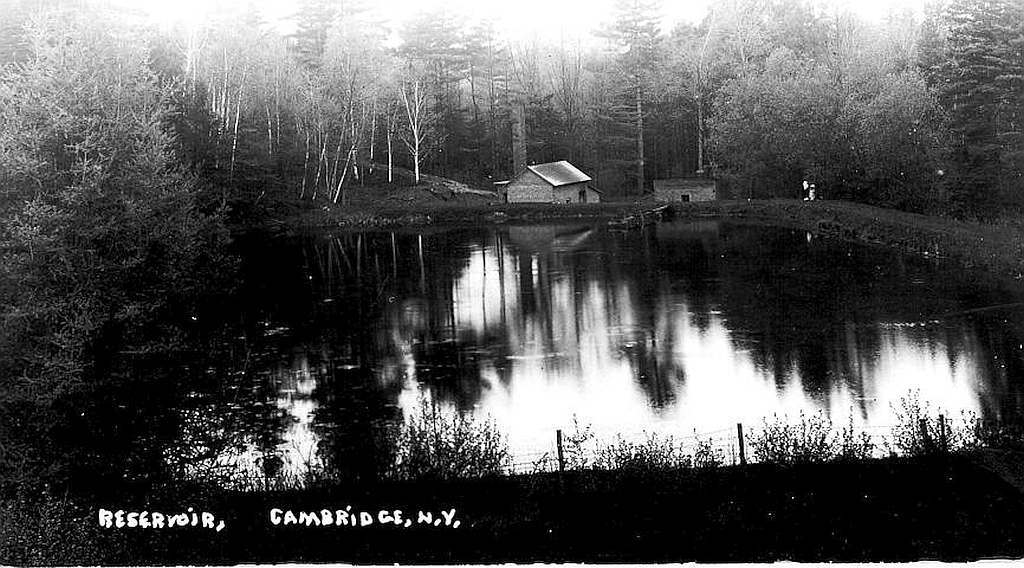

[note: The Cambridge Water Works Company was incorporated in Sep-1885 led by George McKie who lived in the house that is today the Cambridge Historical Society. They used Crocker’s idea of drawing water from Simpson Springs (see photo) at the northwest corner of Rt 313 and Fish Hatchery Road, over 3 miles north of the village. That’s where our village water comes from today. My great grandfather, William Hitchcock, took ownership of the water company around 1900 and immediately upgraded the water mains. The Hitchcock-Gottry’s ran the CWW for almost 100 years until selling it to AquaSource in 1998. Several times during the 1970s and 1980s I met with the village trustees about the village buying the water company. Just like the issues from the 1860s, the village residents of the 1970s and 1980s agreed a municipally owned water company was desirable, they just couldn’t agree how to make it happen].

Although the West End had the Cambridge Creek to fight fires, the creek wasn’t without its challenges. First were the issues of dead carcasses and animal excrement dumped in the creek in Coila (see last week’s article). But there was more. The water flowed behind the homes on the north side of West Main Street, then crossed West Main Street near O’Hearn’s Pharmacy, and crossed South Union Street near Meikleknox. The bridges over these two crossings were always in disrepair. Many a horse had to be shot after stepping through a rotting bridge plank. Carriages and wagons tipped as they crossed the bridges, dumping their passengers into the brook. Some argued that if we had a village, then we’d have a paid road crew to maintain the roads and bridges.

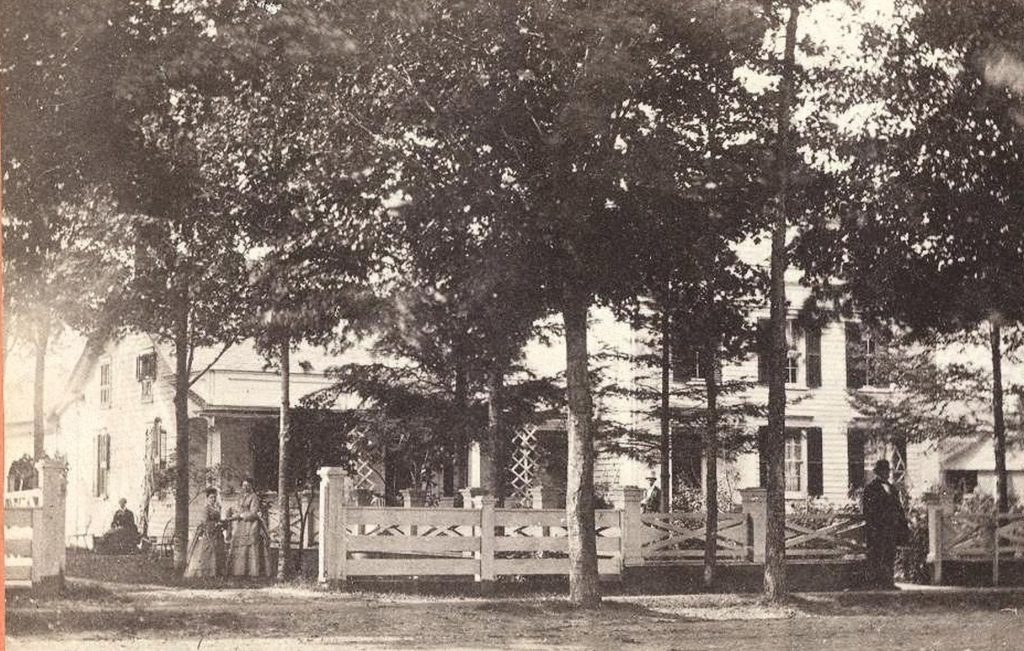

Let’s now take a look at how the barnyard animals on Main Street helped beautify our homes. The Thomas Comstock home (see photo) stood on the south side of East Main Street across from Washington Street. The house was torn down when Grove Street was created in the late 1800s. Notice the fine fence around the house. It was not there as decoration. It was there to keep the cows, pigs, and cattle that roamed Main Street from wandering onto their lawn.

A May 1864 public notice in the Washington County Post newspaper read “Those who are in the habit of pasturing their cows and other animals in the public streets are hereby notified that hereafter we are determined to enforce the law on that subject”.

As the Civil War drew to a close, a new danger came to Cambridge … the bummers. The county was full of strange men, going to or coming home from war. Most were relatively harmless, stealing a chicken here or there, bedding down uninvited in the barn, even doing an odd job or two. But the newspapers were full of stories of “bummers” knocking on a farmhouse door, surprising the wife while her husband was off in the field. There was no local police to “cruise the neighborhood” as they do today.

The residents of Cobb Town (as Plains Road was known) and Pumpkin Hook were always suspected whenever a chicken was missing or a cow was dry of milk. The rowdies from those areas found they could often escape prosecution by blaming the incidents on “the bummers”.

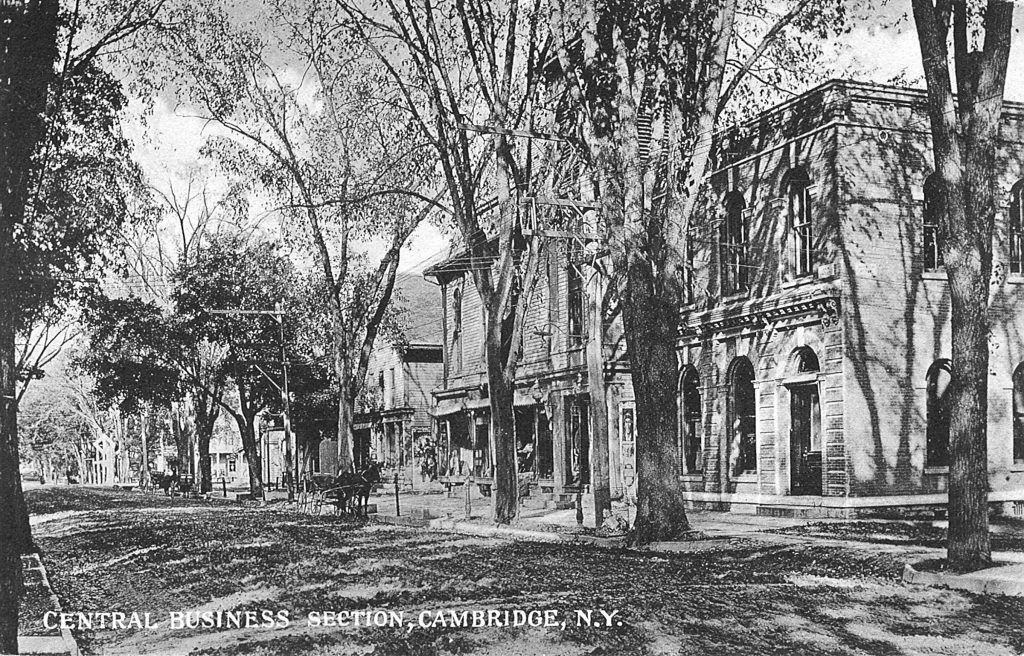

Soon the crimes became more severe. The Cambridge Valley Bank was organized on 15-Sep-1855. Its first building was the brick building on the south side of East Main Street, across the street from Battenkill Books (next to what we old-timers still call King’s Bakery). [note: it wasn’t until the 1870s that the bank moved into the brick building on the northwest corner of Main and Washington streets (see photo), today the home of Roundhouse Café].

In 1865 the bank changed its name to Cambridge Valley National Bank. It was continually broken into, though most times the robbers were unsuccessful in getting any money. In October 1865 the safe held over $70,000, quite a sum for a small community in those days. Burglars broke in, drilled the safe door and packed it with black powder. Fortunately they were spooked and left before blowing the door.

Around the same time the Porter and Higgins dry goods store was broken into. This building is one of the older business structures in the village (1855, I think). Today it houses the Ace Hardware store and is owned by a descendant of the original family who erected the building.

The community was so lawless that Thomas Comstock had $50 stolen from his pants pocket … while they hung on his bedpost one evening as he slept.

The residents agreed something needed to change, but what? The newspaper editorials demanded change, but how? A united village still seemed a long way off when the West End broke into a monstrous fire in Mar-1866. You would think this would be the last straw, the one that finally brought about the incorporation of the Village of Cambridge. But no, nothing came easily when it involved “the Corners” agreeing on anything.