On 16-Apr-2016 the Village of Cambridge celebrates the 150th anniversary of its incorporation. This series explores the events that led to the union of the West End and the East End. So far we’re learned that “the Corners” were physically separated by the Cambridge Swamp and logically separated by churches, schools, and stage coach routes.

Circumstances in Cambridge led to the need for three things that helped set the foundation for unity: a fire department, a police department, and a water company. But, as with everything else in Cambridge, the residents couldn’t agree on how to achieve their needs.

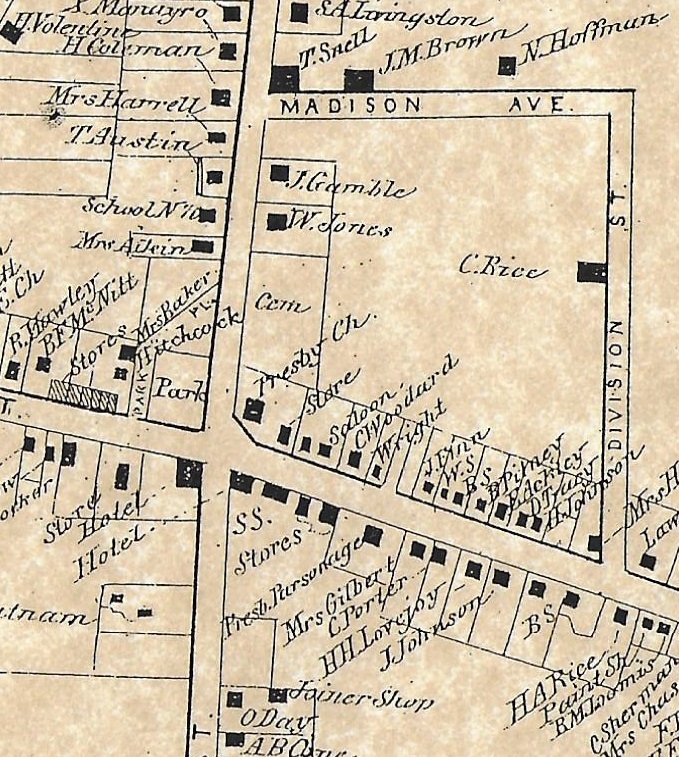

In late July 1864 the blacksmith shop of James Davis caught fire. This was located on the north side of East Main Street between North Park Street and Division Street. That section of North White Creek, as the East End was called, was lined with stores, taverns, and houses.

The church bell at the 1832 Presbyterian Church on the corner (where Rite Aid is today) was rung, this being the fire alarm of the day. Women grabbed their water pails and rushed to help. Men formed a bucket brigade. The East End had no creeks so had to rely on nearby wells and cisterns to fight the fire.

The East End and the West End had many reasons for separation, but when there was a fire everyone came together. West Enders heard the church bells, filled barrels with water from Cambridge Creek and Blair’s Brook (Owl Kill), loaded them onto wagons, and dashed to help the East Enders.

By the time they arrived, Davis’ blacksmith shop was totally engulfed. James Finn’s carriage shop next door was now in danger, but with no firefighting equipment nothing could be done to save it. The men decided they needed a fire break or else the entire East End might go up in smoke. Russell Ackley’s house was demolished, preventing the fire from spreading further.

[note: shown is a photo of Dennis Plunkett’s carriage shop. The photo is from the late 1800s, twenty plus years after the 1864 fire. I believe Plunket’s shop was somewhat in the area of Finn’s carriage shop, perhaps a bit farther east, perhaps nearer the northwest corner of Main and Division streets]

The East End was upset at losing more buildings but also upset that they had to rely on water from the creeks on the West End. However, what made the sting even worse was the arrival of the Salem fire department with their new pumper.

In the early 1860s Charles T Hawley returned home from the California gold rush and assumed the role of station master from his father [more about the railroad in a later article]. Hawley lived in the home on the southwest corner of Broad and First streets, long known as the Station Master’s house.

In 1862 a telegraph line was completed from Eagle Bridge to Cambridge. By 1863 the telegraph line had been extended to Salem, ultimately passing through Cambridge as it ran all the way from NYC to Montreal. Hawley, as station master, was also the telegraph operator.

When Hawley heard the church bells sound the fire alarm on that day in 1864, he sent a telegraph for help to Salem. Within an hour, the Salem fire department had loaded their pumper onto a railroad flatbed and were in Cambridge to help fight the fire. But it was already too late, the East End having lost two businesses and two houses to another fire.

Everyone agreed, Cambridge needed a fire department and firefighting equipment. But how would it be funded: through private subscription or through incorporation into a village? The debate raged for two more years until April 1866. Next week we’ll see how drunkards, pigs, and a circus clown helped people decide that incorporation was the best answer.