On 16-Apr-2016 the Village of Cambridge celebrates the 150th anniversary of its incorporation. This series explores the events that led to the union of the West End and the East End. So far we’re learned that “the Corners” were physically separated by the Cambridge Swamp and logically separated by churches, schools, and stage coach routes.

Last week we talked about the 1864 East End fire that destroyed much of the block on East Main between Park Street and Division Street. The need for a fire department was evident. One way to achieve that was to incorporate into a village, like Salem and Greenwich had done, and create a municipal fire company.

Cambridge was beginning to lean that way but Dorr’s Corners (Gilbert St), the East End (Park Street), Cambridge Corners (Union Street), Wendell’s Corners (Academy Street), and Stephenson’s Corner’s (Coila) still didn’t like or trust each other. They needed another reason to unite.

The next reason the residents found to unite was the village odor. In 1864 our local Washington County Post newspaper declared our streets “a public barnyard”. The odor of dead carcasses was very strong in the middle of the village. One reason was the two tanneries in Coila [note Stephenson’s Corners changed its name to Coila around 1850 when the post office was opened there].

James Robertson’s estate, today known as Maple Ridge, (see photo) was across the street from his tannery pond at the west edge of Coila. Dead carcasses were dumped into the Cambridge Creek. As the creek flowed toward the village, it passed by a second tannery pond that was located at the intersection of West Main Street and Center Cambridge Road (County Route 59).

More carcasses were dumped into the Cambridge Creek. The creek then flowed behind the houses on the north side of West Main and headed toward the West End businesses. Cambridge Creek flowed under West Main Street near what until recently was O’Hearn’s Pharmacy. The creek then crossed South Union Street near today’s Cambridge Guest Home (Meikleknox).

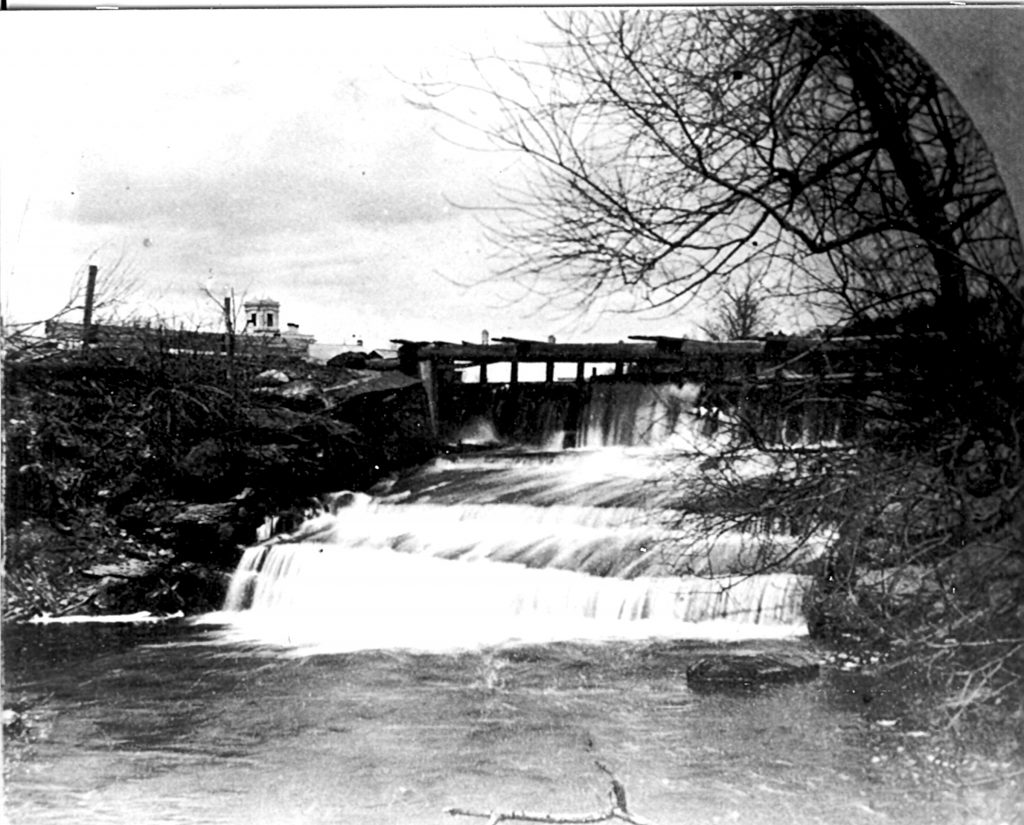

That’s where the problem occurred. Blair’s Brook (Owl Kill) joined the Cambridge Creek behind the Old School (the south end of the Cambridge Library lawn). Blakeley had a dam there (see photo) and the carcasses, and their foul odor, got hung up in the dam. Remnants of the old dam can still be seen in the swamp behind the houses as you look eastward from South Union Street.

The residents needed a unified village, with a set of laws that everyone had to follow. It was not uncommon for village residents to dump dead carcasses (pigs, sheep, and cattle) by the side of Main Street. [This had become such a problem that when the Village of Cambridge was finally united in April 1866, one of the first by-laws created by our village trustees was “any person to throw or put any filth or nuisance, such as a dead cow or horse, in any street … shall be fined $1 per offense”. That was equal to one day’s pay in the 1860s]

In addition to a common set of laws to control animal waste, the residents also began to feel the need for a police department. Some incidents were troublesome but harmless while others were more severe.

One of the former events occurred in the summer of 1864 when two “fine young gentlemen from the village” wandered out of one of the many saloons along Main Street and stumbled into a prayer service in the Embury Methodist Church. They innocently sat in a back pew, occasionally disrupting the meeting with shouts of “Hallelujah” or loud snores.

The Cambridge Methodist church was created as the second Methodist congregation in America by Philip Embury himself. Two of the tenants of the early church were no card playing and no drinking and yet, here right in the middle of a group of Methodist women at prayer, were two drunkards. But there was no one to call, no police force to come to the aid of the Methodist women.

The need for a police force became a hot topic in the summer of 1863 when a circus rolled into town. They came by rail from Fort Edward and began setting up the tents on “The Grounds” in front of the railroad depot.

John Hubbard owned the lumber yard on the south side of Main Street just east of the railroad tracks (the Agway building in the 1960s). As Hubbard walked home that night, he noticed “The Wheel of Fortune” had been set up near the circus tents. Gambling was not allowed in “the corners” but there was no police force to call so Big John Hubbard took things into his own hands. Hubbard stormed into the tent and kicked over the gambling table.

Sam Stickney was a popular clown with the circus and he made a nice side income by running his gambling tables wherever the circus pitched its tent. When he learned that Hubbard had destroyed his gaming table, he stormed out looking for revenge.

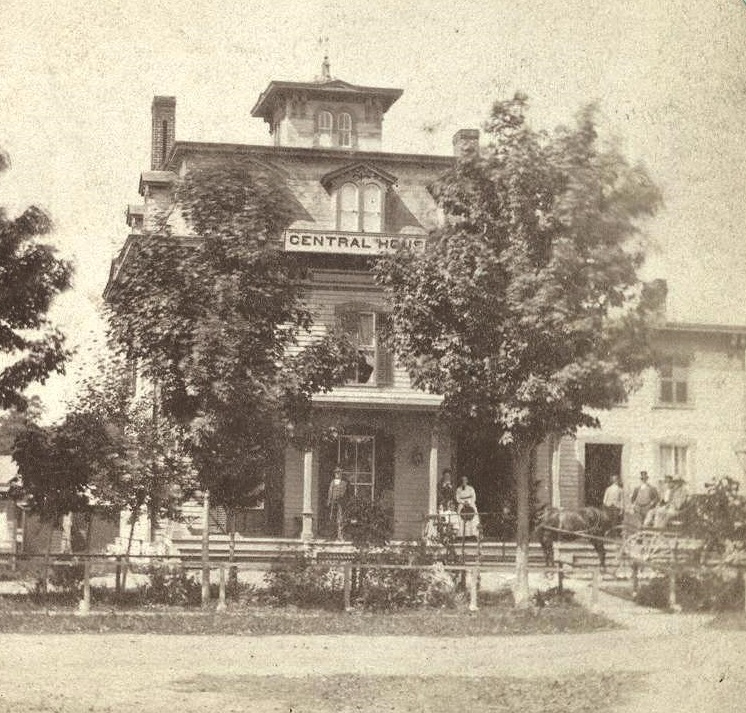

Stickney rushed to the Central House, a hotel located on the southwest corner of Broad and First streets (see photo). There he found Hubbard in the barroom. All of the circus people who were staying at the Central House heard their colleague was in trouble. They grabbed knives and bottles and headed to the barroom. Local residents sent out a cry to come help Hubbard fight the clown.

In seconds the barroom was a field of battle with chairs, tumblers, pitchers, spittoons, and other furniture being violently hurled about. Hubbard was stabbed and the circus troupe escaped out of town on rail. Constables Weir, Rice, and Chappel tried to sort of the mess, but without a unified set of laws to guide them little was ever done.

The residents agreed that a police department and a common set of laws were needed to reign in the wildness that was found on the streets of Cambridge. But that would mean “the corners” would have to unite and the residents still distrusted the folks at the other end more than they feared the lawlessness on the streets. Next week we’ll see how the 1866 West End fire finally convinced people that a union may be necessary if Cambridge were to survive.